Inside Health Economics and the Forces that Influence Health Care

They call it the “Fauci Effect.” According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, the number of medical-school applicants increased by 18% in 2020, compared with the previous year. This record number of potential “docs in training” is in part due to the elevated profile of health figures like Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and frontline doctors and other health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. The University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine reported a more than 20% increase in applications in 2020 compared with the previous year.

Guy David, Wharton’s Gilbert and Shelley Harrison Professor of Health Care Management, has been watching these numbers with interest. While as a professor of medical ethics and health policy at the Perelman School of Medicine, it’s encouraging for him to see more aspiring clinicians, he also wants the next generation of health professionals to look beyond the stethoscope as you consider having an influential role on society’s health.

“A lot of people who are drawn into the health care space want to have an impact on people’s well-being,” notes David, who admits that he might have chosen to be a doctor when starting his career if he didn’t faint at the sight of blood. “One of the drivers that people have when they go into medical school is that they really want to make a difference in people’s lives. What we’re seeing now…is that there are a lot of ways to make a difference and impact people’s lives without having them remove their shirts to put your stethoscope on them.”

“You can be a patient advocate even if you’re in finance, economics, marketing or management.” — Dr. Guy David, Wharton Professor

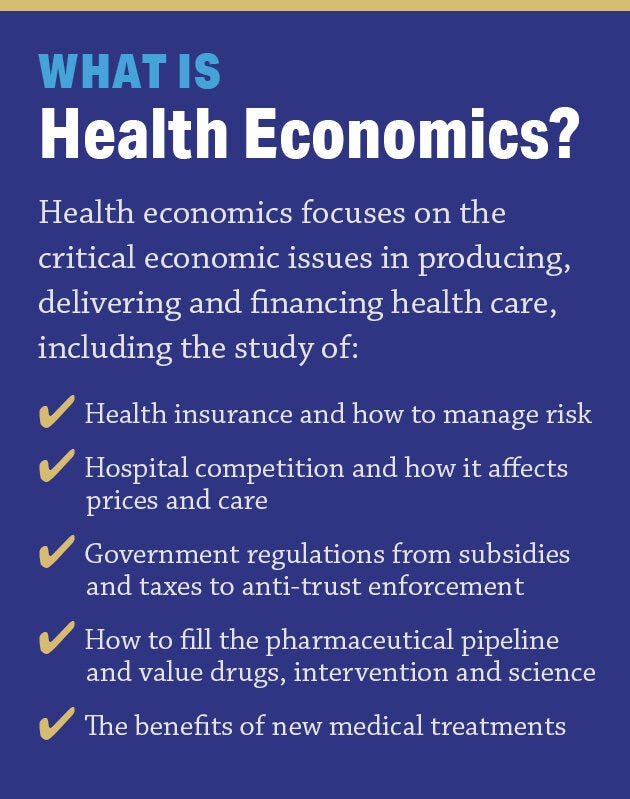

One of those ways is health economics.

If you’re like most high school students, you’re not sure what health economics is all about. For example, Sophia R., a 16-year-old from Philadelphia who recently wrapped up a health-related internship creating hand-washing campaigns for global communities impacted by the coronavirus, said she learned a lot about the field of public health. When we asked her about her interest in health economics, she said: “What exactly does that mean?”

She’s not alone. So, we turned to Professor David, an expert in health care management who has also designed a health economics course for our new Wharton Pre-Baccalaureate Program for high school students, to help us figure it out.

Health Economics Defined. Health economics applies economic concepts to the health care sector, as it often tries to confront the most pressing challenges facing the health care system. Economics is the study of how to allocate scarce resources to satisfy human wants. Health care is a massive ecosystem that is driven by four main groups. They are: the people and institutions who provide health care, like nurses, physicians, hospitals and nursing homes; the health insurance companies, like Medicare and Medicaid and commercial companies; the producers, like device manufacturers and pharmaceutical companies; and the regulators, like the government, that supervise health-care activity.

“Health economics marries the concepts of how to allocate scarce resources to satisfy human wants, with the complicated details that combine this ecosystem of providers, payors, producers and regulators,” notes David. “Health economists can be more on the supply side, so they might be interested in how hospitals behave, and prices. Or they can be on the demand side and study why people are obese or what happens to individual behavior when we tax cigarettes.” Among the student research projects recently funded at the University of Pennsylvania Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics: “How Do Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs Reduce Opioid Prescribing?;” “Housing Affordability and Health Outcomes;” and “An Analysis of Healthcare Utilization Amongst Undocumented Patients.” Fellows at LDI study everything from health insurance and medical decision making, to access and equity and innovations in health-care delivery.

Studying Tradeoffs During the COVID-19 Pandemic. The economic concept that resources are scarce compared to their uses is fundamental to understanding the field of health economics. People have different ideas about how to use those resources (like money), and even more so during a global health crisis. Inevitably, there will be tradeoffs – you will give up something to get something else in return. What is the right balance? Health economists are trying to figure that out with all the forces that influence health care as they help guide decision-makers.

Questions might relate to how much personal protective equipment hospitals should buy, or they might look more broadly at profound economic issues affecting society. “There is an active discussion right now around the value of life,” explains David, who has been working on several pandemic-related research projects for private industry. “We’re trying to understand given the fact that this is a deadly virus, how much risk are we willing to take as a society. When we are opening up the economy, we are positively affecting the livelihoods of people. On the other hand, we are exposing people to risk. Where do we find the right balance? That’s all economics; finding that balance. It’s easy to say that we all shelter in place and study remotely, do our work online, and if we have children going to school, each will sit on their computer. But what happens if you’re a family that doesn’t have Internet and your kids are all in the same room? Anything on this continuum is exacerbating the inequality that we already have in society…So we’re going to order things on Amazon and have them delivered, but somebody is delivering those things. That is their work. You can call them essential or non-essential workers, but those workers are putting themselves at risk in various ways. This area of understanding inequities and wealth distribution is something economists do.”

A Big Experiment. In many ways, the pandemic has given researchers like David the opportunity to study issues that they’ve been interested in for years. For example, practically overnight providers had to switch to telemedicine, or providing health services virtually — something they have long resisted. And what about patients who received a knee replacement in the days leading up to the lockdown, and then those who were suddenly forced to wait for their replacements when people were discouraged from leaving home? How did the treatment or lack thereof affect people’s health? “The pandemic created that natural experiment where some people were lucky and got the surgery and some people were unlucky and just couldn’t get it. We can study what happens with them,” says David. “The pandemic has disproportionately affected disadvantaged people, it has disproportionately affected people who lost their jobs, it has disproportionately affected people who needed care and had to get it virtually. It gave us the opportunity to shed some light on these issues and get some very important variation that we didn’t have before.”

How Health Economists Think. It’s an analytical field, notes David. “I think it’s very different than, for example, studying medicine, where there’s a lot of memorization and a lot of things that you need to remember,” he says. “There’s not a lot to remember in economics, but you have to learn to think like an economist and you have to have a very strong analytical toolbox. We are doing cutting-edge modeling, which is all mathematical. We’re doing a lot of work in statistics and a lot of measurements and estimation. We talk about revenue, we talk about cost, so you have to build a lot of financial acumen to do some of those analyses.” At the same time, he adds: “It takes a certain person who is passionate about this world to be successful.”

While excited to see all the aspiring doctors, nurses and frontline workers, David wants future medical professionals to understand that many industry leaders are not the people wearing scrubs.

“You can be a patient advocate even if you’re in finance, economics, marketing or management,” he says. “You can come up with processes, innovations and ideas that will make health care more accessible, higher quality, more transparent, cheaper and more available. If you can do that, you will have impacted so many lives without touching a single patient. And even if you want to be a clinician, knowledge of health economics is still very valuable. You need to understand where the regulations are coming from and you need to understand why people are asking you to do things in a certain way. It’s always a good idea to take a course in health economics or study health management as a complement to being a better clinician.”

How does the basic economic concept that resources are scarce compared to their uses fit into the world of health economics?

How do you feel about Dr. David’s assertion that you can have a profound impact on people’s health without becoming a doctor? Do you agree? Why or why not?

What does it mean to think like an economist?

What health-related issues would you like to tackle as a health economist seeking to find that important balance? Share your ideas in the Comment section of this article.